Trauma-Informed Peer Support – Creating Stories

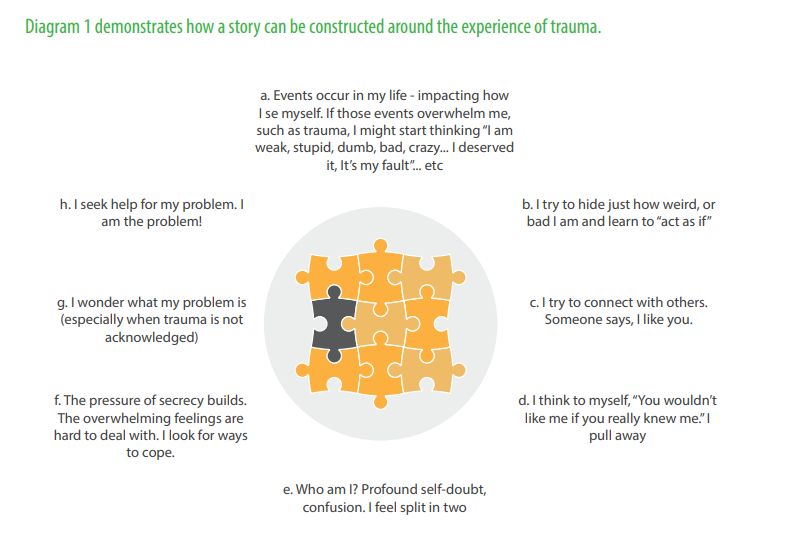

Our past experiences create personal stories about who we are. Our stories help us define ourselves and include our beliefs about the world and others, what we think of as true, our interpretations of events, and the meaning we make out of what has taken place in our lives. Our stories are true for us and guide what we do. The following series of diagrams are designed to help us understand how we construct our stories, particularly around the experience of trauma. They show how our stories impact on how we interact with the world and how cycles can develop. They also help us think about what we can do to help each other evolve new stories. When you look at them, do keep in mind that the points made in the diagrams are deliberately exaggerated to help illustrate key points.

Firstly, trauma can impact on our connection to ourselves. We might begin to experience ourselves as damaged, unworthy, dirty, bad or crazy. Perhaps we feel that we deserve the events that have taken place, or perhaps we come to believe that if we had been stronger we could have handled the events.

Trauma can also impact on our connection to others and peer support workers should be particularly aware of this. Trauma can call into question what relationships mean. We can conclude that we don’t deserve much, or that we don’t have the right to expect love, or respect, or to be treated with dignity.

The dynamics of trauma can be subtle or extreme. Forming healthy, meaningful relationships with others when your story is about being undeserving can be hard. This leads to people backing away or maybe doing something to get others to go away, or to prove just how bad you really are.

The overwhelming feelings that are associated with trauma, and the conflict around making a connection with people can result in coping strategies that are less than healthy. In some cases it is people’s coping strategies (for example, self-injury, substance abuse or risky sexual behaviour) or their adaptations to trauma (for example, profound distress, suspicion, fear, dread or feeling like dying) that bring people to mental health services.

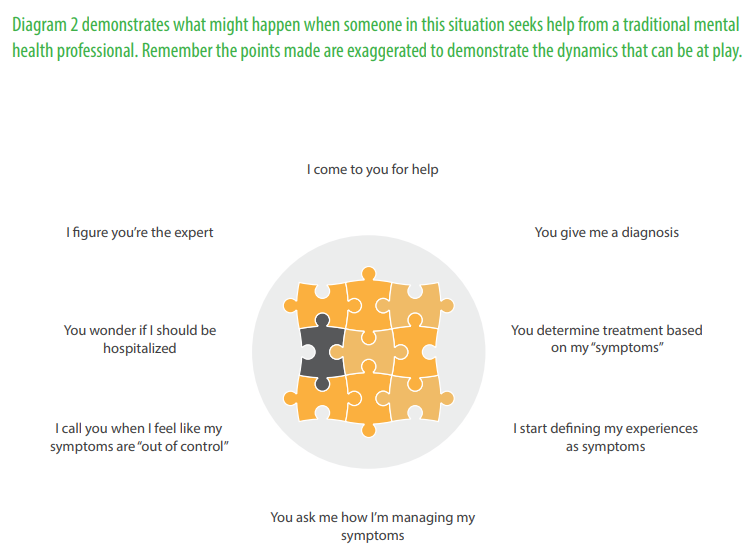

In our culture, when we have any emotional conflicts we are most likely to be offered mental health support. When this happens, usually the first interaction is about assessing needs to reach a diagnosis. This evaluation and assessment is designed primarily to answer the question, ‘What’s wrong with this person?’

From a trauma-informed perspective this is, in many respects, an odd sort of first conversation to be having, since so much of ‘what’s wrong’ has to do with what has happened to the person. The result of this initial assessment might be to reinforce the idea that there is something wrong with the person that can be diagnosed (given a label or a name) and treated.

The trouble is that once a diagnosis has been made then experiences become defined in the language of symptoms. The treatment and support that is offered is based on the symptom cluster within the context of the agreed diagnosis.

This can result in people confusing all kinds of feelings with symptoms, and even getting to the point where they do not know the difference between a feeling and a symptom. This is reinforced in treatment relationships, when you are regularly asked how you are managing your symptoms.

In many ways, relationships in the mental health system have encouraged people to focus on what’s wrong with them. Treatment relationships can prevent people from exploring what is happening and could actually be causing distress as they are encouraged to rename experiences as symptoms rather than to understand them as potentially normal reactions to abnormal events.

In this situation it can people can feel vulnerable and fragile and are less likely to question authority. They have established other people as the expert (you are sick, and you cannot trust your judgement), and cannot do anything but listen to their interpretation of what’s going on, and take their advice?

As peer supporters our aim is to create different conversations and different responses. But peer support has some unique challenges when operating within formal mental health services, and we will examine some of these in more detail in modules 10 and 11.

Employing organisations require peer supporters to follow policies and protocols. It is therefore important for you not only to understand your responsibilities but also to bring this understanding into your conversations with the peers you are supporting, and to discuss your role and organisational responsibilities at an early stage.

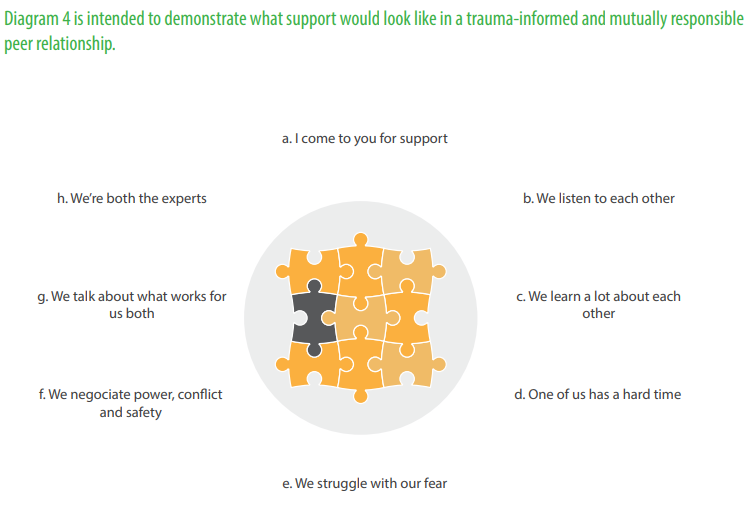

In diagram 4 both parties have listened to each other and clarified roles and responsibilities and you can really feel mutuality in the relationship. But what happens when things start to wrong? Perhaps one is having a really hard time. Perhaps the person being supported is not feeling great and is acting in a way that scares the peer supporter.

In this scenario instead of talking immediately about safety (as in diagram 3), the peer supporter actually struggles with their fear, and names it if they need to. The conversation is about what both people in the peer relationship need and what works for both in a way that keeps both in the conversation. The result is that both come away feeling like experts.

When this kind of conversation is ongoing and practised, the focus is no longer on symptom management but rather on what’s going to make the relationship strong, reciprocal and healthy. To support this scenario we might also have conversations in advance about what might happen should one or the other of you get scared or uncomfortable. So in trauma-informed peer support, the goal is to build relationships where you try to understand, tryout new ways of relating, take risks by being honest or pushing your discomfort and by negotiating what will be of benefit to you both.